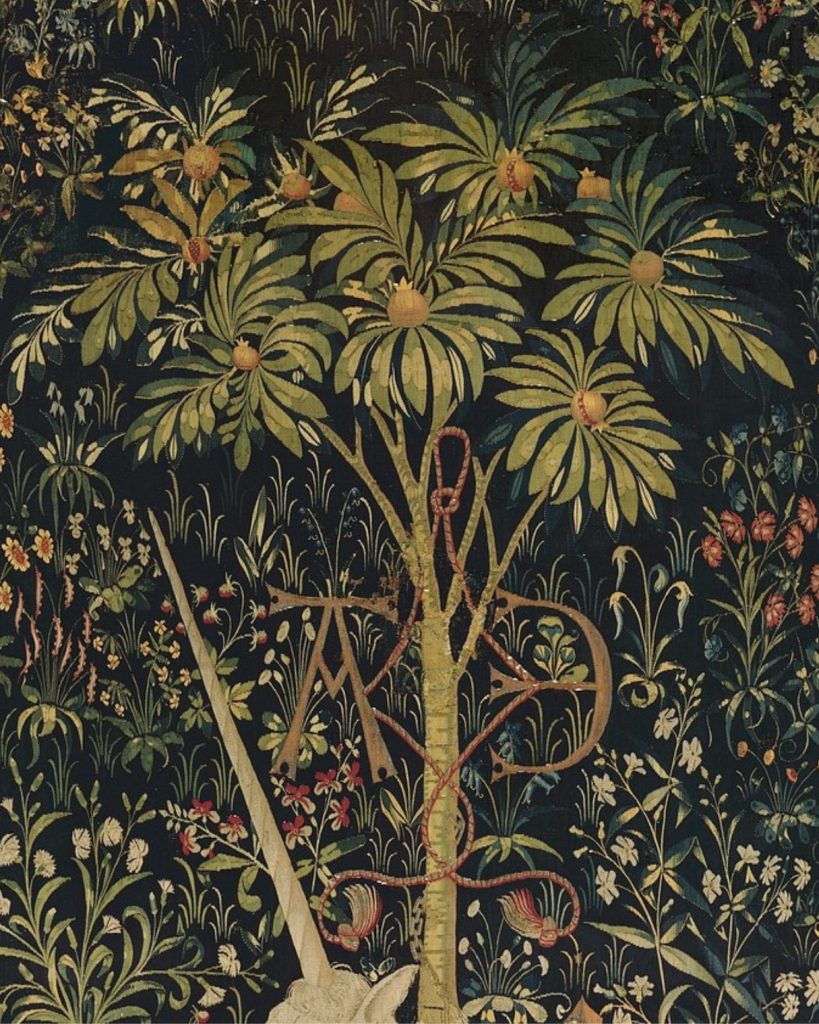

The Unicorn Rests in a Garden, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain.

When we think of nature, we often conjure a landscape shaped by vegetation—dense rainforests, vast tundras, mysterious wetlands. Whether lush or barren, plants are the foundation of life, the first stirrings of creation. After a long, moist night, the world awakens with the force of wood—Qi rising, stretching toward the sky, filling the air with the quiet hum of growth. Wood is embedded in our collective consciousness as a symbol of renewal, resilience, and the flourishing cycle of life.

I have long been drawn to the contrast between the four classical elements and the Eastern philosophy of Wu Xing, the Five Elements. While the Western system—fire, earth, air, and water—seeks to define the material composition of existence, Wu Xing offers a more dynamic framework, one that mirrors human interaction with the natural world.

In both systems, fire, earth, and water remain constant. Yet, in Wu Xing, metal is separated from earth, and wood replaces air. This substitution is profound—it marks a shift in focus from the intangible to the tangible, from the heavens to the soil. Air is unseen and ethereal, while wood is something you can touch, shape, and cultivate. It does not merely exist in the world; it builds the world.

This replacement of air with wood reflects a later stage in human development. The classical four elements belong to an age when people looked to the sky, wondering what the universe was made of. Wu Xing belongs to an era when people turned their gaze downward—toward the soil beneath their feet, toward the tools in their hands. Civilizations did not rise through air and earth, but through wood and metal. Forests provided shelter and fuel, while metal, extracted from the earth, gave humans the power to carve, craft, and construct.

Though the four-element system continues to shape Western thought, it too has evolved. Alchemy and herbalism redirected attention from cosmic speculation toward understanding human society, mirroring the same shift that Wu Xing embraced. Both frameworks contributed to traditions that emphasized recorded knowledge and craftsmanship, reflecting an evolving relationship between humanity and the natural world.

The Qi of wood is both forceful and supple, pushing upward and outward, yet flowing harmoniously with the wind. Like all elements in Wu Xing, wood is divided into its Yin and Yang aspects—two energies that shape not just the nature of plants, but the very essence of life.

There are countless ways to interpret these dualities. I see Yang wood as the trunk of a tree—strong, upright, unwavering. It is the foundation of life, the skeletal structure upon which all else is built. Yin wood, in contrast, is its branches, leaves, and flowers—the delicate, reaching, ever-changing parts that seek light, spread seeds, and sway with the seasons.

Yang wood is the bone; Yin wood is the nerve. Yang wood holds form; Yin wood forms connections. Together, they sustain the life of the tree, and in doing so, they reflect the forces that shape us all.

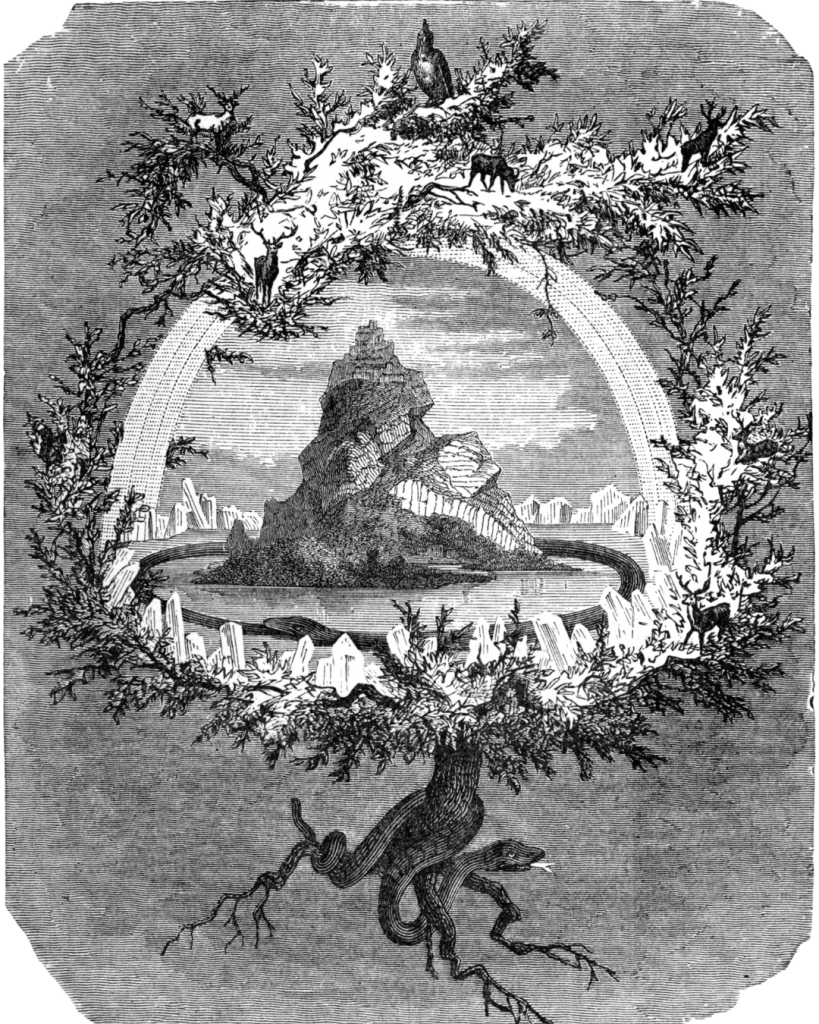

The image of the “World Tree” appears across cultures, bridging the divine and the mortal realms. In Norse mythology, the entire cosmos is conceived as an immense ash tree—Yggdrasil—whose roots and branches connect all planes of existence, from the underworld to the heavens. In Mesoamerican traditions, world trees take on different forms depending on their environment. Early interpretations of the Mayan world tree pointed to the kapok tree (Ceiba pentandra), a towering giant of the rainforest. Others identified the cosmic tree as maize (Zea mays)—a staple crop, or the water lily, a plant rising from the aquatic underworld.

The Ash Yggdrasil by Friedrich Wilhelm Heine, Public Domain.

World trees are never merely imagined constructs; they are reflections of real, living species. Not all civilizations needed to choose towering giants to represent the foundation of life. Instead, they turned to the plants most vital to their survival and wove them into their mythologies, transforming them into symbols of divine order.

Some trees alive today predate the rise of human civilization, standing older than Stonehenge and the pyramids. That is the spirit of Yang wood—enduring, immovable, a wisdom-keeper rooted in the depths of time.

Yet Yin wood, with its ephemeral beauty, is just as powerful. It is the olive branch carried by a returning dove, the oracle inscribed in the rustling of leaves. It is life in its most generous form—flowering, fruiting, nourishing all who seek it.

Yang wood roots us in time; Yin wood teaches us how to appreciate it.

Wood stands at the crossroads of life and environment—unlike any other element, it is both a force of nature and a living presence.

According to Wu Xing philosophy, the gods of wood rule the season of spring—when life surges forward, breaking through soil and snow, unfurling into green. Spring is a time of momentum, fierce competition, and relentless expansion—an untamed force eager to claim its place.

But growth comes at a cost. As plants awaken, so do parasites. As warmth returns, so does disease. The delicate balance between life and decay tilts precariously, especially amid today’s chaotic patterns, where new life often emerges fragile, unguarded, and uncertain of its fate tomorrow.

One of the most significant moments of spring is Jīngzhé (惊蛰), “The Awakening of Insects.” It is the day when hibernating creatures stir, when the earth’s pulse quickens, when the air itself seems restless with movement. The plants are ready; their companions emerge. The world grows noisy again. The winds carry the scent of adventure, and everything—every living thing—is hungry for something.

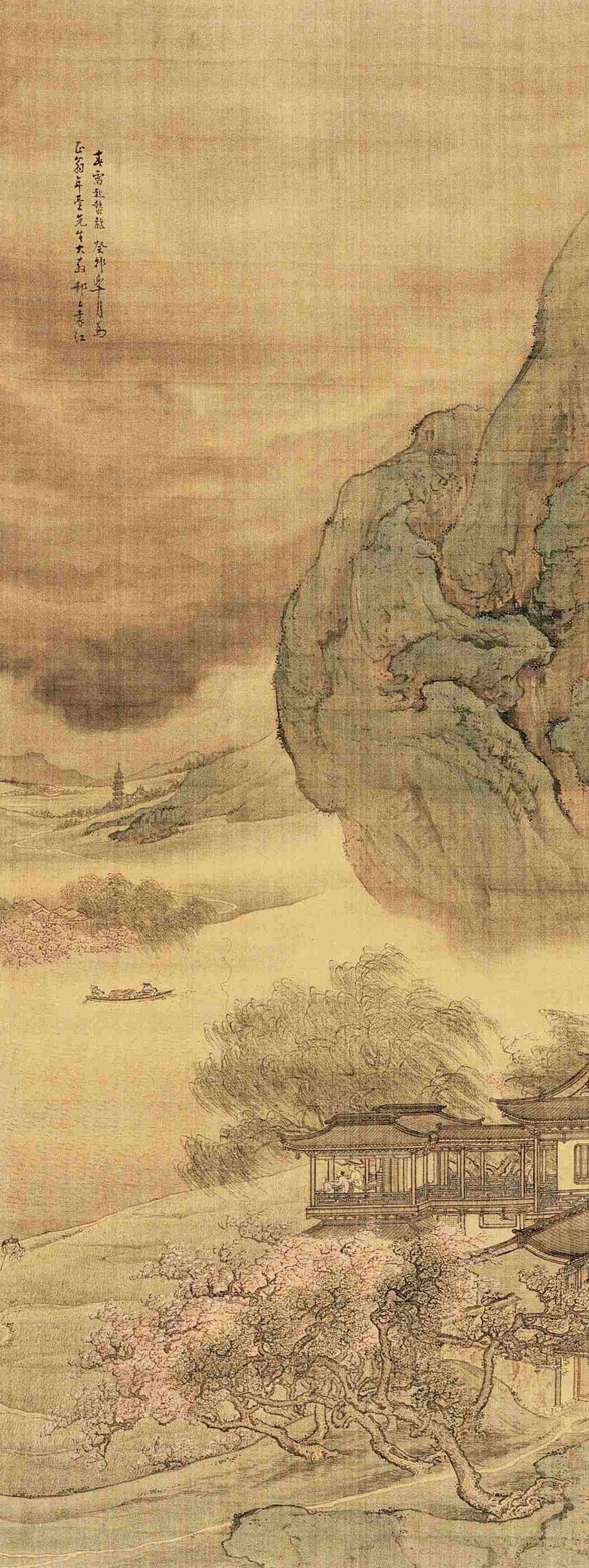

春雷起蛰图 by 袁江 (Qing Dynasty), Public Domain.

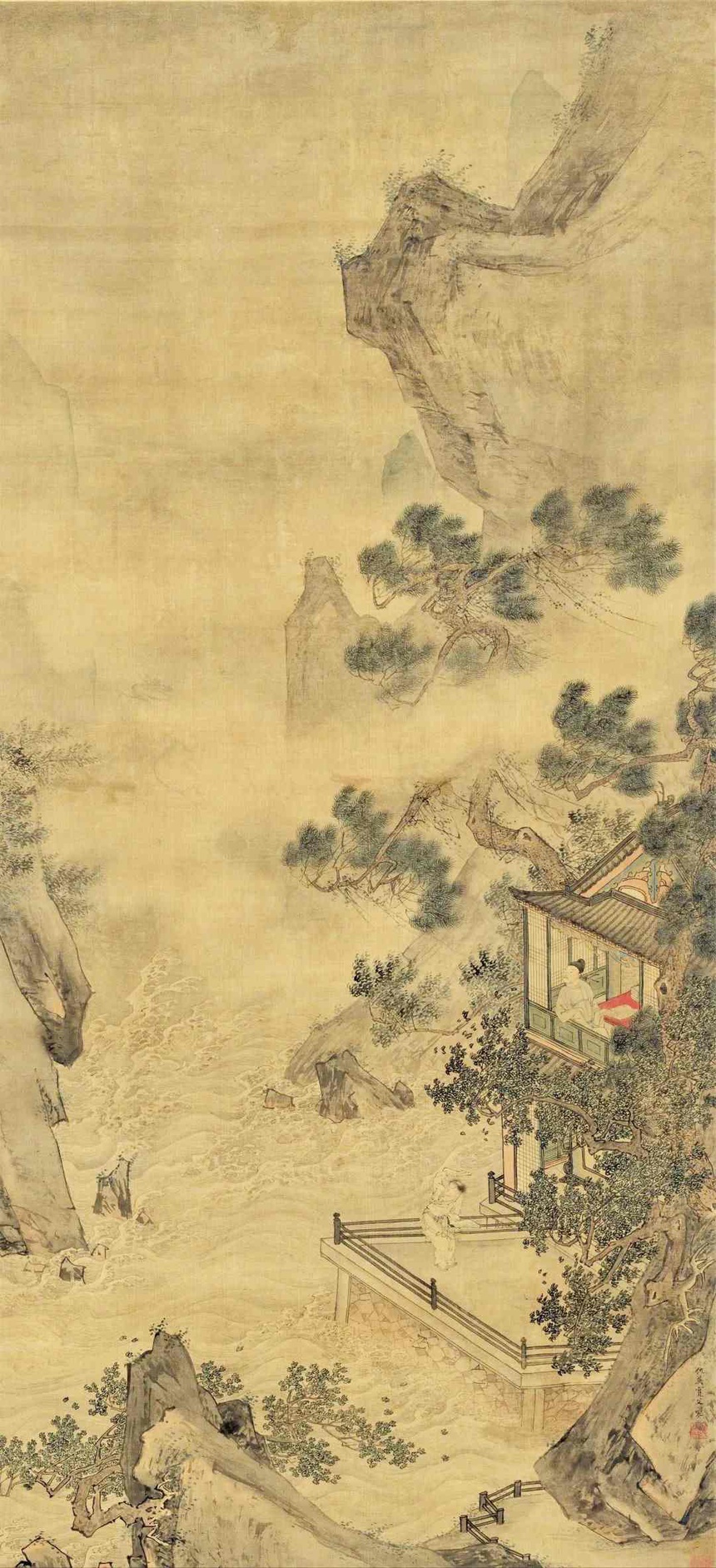

春龙起蛰图 by 仇英 (Ming Dynasty), Public Domain.

It is human nature to be captivated by the atmosphere of spring. The eco-self awakens, stretching toward the vastness of the outside world, longing to dissolve the exhaustion imposed by the ego-self. Now it’s time to listen—to the wind, to the shifting air pressure, to the tremors in the soil. It is time to observe, to heed nature’s unspoken warnings, and to align ourselves with the symphony of co-existence. Follow the green footprints of the wind, step into the rhythm of the future.

Leaves are nature’s messengers, whispering to humanity the secrets of preserving and transmitting knowledge. Eastern philosophy defines the Qi of wood not only in plants but within anything composed of natural fibers—strings, brushes, paper, furs, feathers—each marked with intricate lines and unique textures. These fibers carry nature’s subtle intelligence, gently and vividly connecting us to the symphony of the living world, reminding us of what we are, and what we might yet become.

Writing, therefore, is an act of wood. Each sentence is a seed we scatter, hoping it roots deeply in another’s mind. We plant and harvest words endlessly, driven by an instinct older than thought itself. Encoded within us is a better self, guiding us with a creative urge—to reach out, bridge distances, and touch unseen worlds.

I believe language is composed of all elements: Fire ignites creativity; water flows in endless exchange; metal conveys precision and enduring meaning; air grants boundless freedom; earth provides grounding and reality. Yet among all these ancient elements, wood moves me most deeply—with its relentless aliveness, its quiet generosity and tenderness, and its sacred power to connect us, long after our own lives have passed.

When tracing the linguistic roots of words, I often glimpse something familiar, something I’ve always sought without realizing it. Even when exploring languages neither my first nor second, their ancient origins appear beautiful, intuitive, strangely known. In those moments, I feel touched, elevated beyond my current self. Perhaps this resonance arises from something as tangible as neuroplasticity—my brain echoing with recognition, flexibility, discovery. Or perhaps it emerges from somewhere more romantic, from myth and dreams, from unconscious scripts running beneath our waking lives.

Linguistic roots strengthen my belief in endless possibility. Language itself is a living forest, filled with dreamlike fragments from distant ages. Fatalism becomes tolerable, even poetic, when we realize how much remains to be rediscovered.

Plants have given us everything from the beginning, but what have we offered in return? Are we creatures worthy of the world they sustain?

Throughout history, we’ve used animals as symbols of strength, wisdom, and survival. In Wu Xing, the god of Yang wood is represented by the tiger—or any feline gracefully navigating branches. The god of Yin wood is the rabbit, a gentle creature thriving on grass. These animal deities are more than symbols; they reflect the profound artistry of ecological niches—the subtle ways creatures shape and are shaped by their environment.

Some examples fascinate me: the panda’s fingers, meticulously shaped by evolution for the sole purpose of grasping bamboo; the sloth, whose life moves in rhythms dictated by the leafy canopy. These animals have evolved not merely to coexist with plants but to embody and depend upon them. They have developed a quiet devotion to their surroundings—a wisdom that humanity has gradually forgotten.

Unlike them, we are not passive dwellers of our environment. We don’t simply accept what is given and thrive within natural limits. Instead, we have learned to alter our surroundings, overriding even the biological codes written into our genes. Our ancestors took shelter beneath trees, marked seasons by their leaves unfurling and falling, and measured time by listening to the murmurs of plants. We harvested their fruits, wove their fibers, and carved our histories into their dead bodies.

Sappho and Alcaeus by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Public Domain.

Yet we have also taken more than we have given.

If pandas were shaped by bamboo, what shapes us now? The flickering glow of screens? The endless repetition of manufactured narratives? When was the last time we genuinely listened to the trees?

We read books, enter libraries, sustaining our dreams and hopes among the remains of dead wood. But I am certain we must hear the voices of living plants—their insights, their warnings, their quiet wisdom. They are not echoes of the past; they live fully in the present, silently narrating their experiences of this very moment. To honor them is not simply to admire their stillness, but to recognize their rightful place as nature’s firstborn, the most sacred inhabitants of this earth.

We should listen—not just for their sake, but for our own.

Plants measure time in centuries; their patience extends far beyond our transient anxieties. They stood here long before us and will endure long after we vanish. If wood carries memory, what do forests remember about humanity? Will the kindness of a few good-hearted sapiens ever be enough to protect their ancient legacy?

Explore other elements