When we search for life beyond Earth, we seek water first. Water, is the essence of existence itself.

Astonishingly, the water on our planet is older than the sun. Within each drop—whether oceans, rivers, clouds or coursing through our veins—there lies ancient cosmic history. We cannot speak directly with this water, but in humbler moments, we sense its truth: our thoughts and dreams flow from solutions far older and wiser than our consciousness.

Everything we cherish, from the vibrancy of nature to the intricacy of human cities, depends entirely on water. We ourselves are primarily water. Culturally, water is closely associated with women: they bear life, nourish infants, and sustain communities. Observing water’s rhythmic cycle—flowing through rivers, ascending into clouds, returning as rain—we recognize our own lives echoed within this gentle rhythm. Quietly, inevitably, we return what was once given.

Thus, water becomes the current of being, a subtle measure of our lifetime.

Oceans, rivers, lakes, rain, snow—all forms of water silently shape our existence. In Wu Xing (五行) philosophy, water’s color is black, mirroring oceanic depths and invisible mystery. Water rules nighttime and winter, representing darkness—fire’s opposing force. It must be black, for water arises from the enigmatic chaos of the cosmos, the void where life both begins and ultimately returns.

Born from warm water in the womb, our lives commence with immersion. From that instant, we begin a quiet cycle of return. Each breath, heartbeat, and moment of emotion gently releases the water gifted to us at birth. Aging is merely the slow drying of this invisible stream—a gradual giving back to the world.

I cannot help but think of Lin Daiyu’s tears.

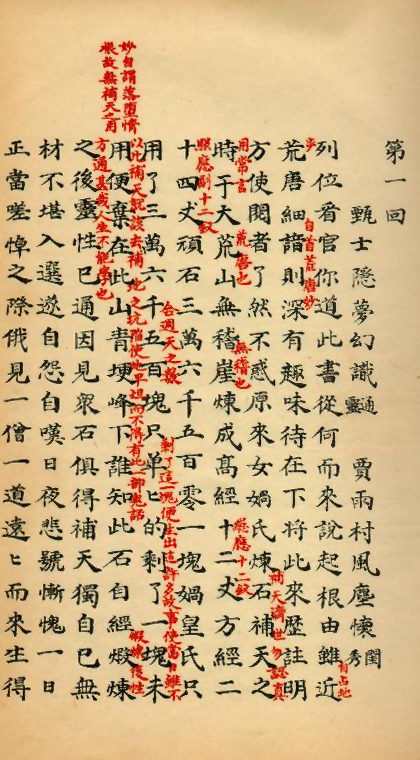

红楼梦图册 by 孙温 (Qing Dynasty), Public Domain.

In Dream of the Red Chamber, Lin Daiyu is no ordinary girl. Born into nobility shadowed by tragedy, she takes refuge in her uncle’s household, growing up alongside her cousin, Jia Baoyu. From the moment they meet, they are soul-bound—drawn to each other by a love that seems to precede time itself.

Yet their earthly connection is only half the story.

In her preexistence, Daiyu was the Crimson Pearl Immortal Herb (绛珠仙草), rooted beside the Three-Lives Stone along the Spirit River in the west. There she was nourished by divine dew from Shen Ying Shi Zhe (神瑛侍者), a celestial attendant. Over ages, Daiyu absorbed heaven and earth’s essence, shed her botanical form, and became a celestial maiden—freely roaming the heavenly realms.

But the memory of this divine nourishment lingered. When Shen Ying chose to descend to the mortal world—as Jia Baoyu, second son of the House of Jia—Daiyu followed, driven by an entanglement of gratitude and romantic longing she could not unravel. “He gave me dew,” she resolved. “yet I have no water to give in return. I will repay him with a lifetime of tears.”

Their bond is recorded as the Wood and Stone Vow (木石前盟). She, born of wood; he, carrying the sacred stone left by Nüwa, the mother goddess who mended the heaven.

Thus, her fate was sealed. Daiyu entered the world steeped in memory and sorrow, her destiny was to weep.

From their first encounter, Baoyu became a captive to love. But misunderstanding shadowed their connection. Baoyu was passionate toward all things; Daiyu devoted to one. As the family declined and Baoyu had witnessed farewell after farewell among those dear to him, Daiyu’s health faded. Her tears, once endless, began to dry. And when the last drop fell, so did her life. Her mission—the slow, aching repayment of water—was complete.

This story has haunted me since childhood. Its sorrow, singular devotion, and the inevitability of fate shaped my understanding of universal love. It etched its way into my faith and behavior, leaving me an incorrigible idealist.

And it makes me wonder: when we are born, whose gift are we returning? Who once gave us breath, and mind, and form? And how might we repay such gifts?

We grow our emotions, we learn to let them go, slowly, painfully, until we are ready for everything—even our final dreams flowing silently into eternal waters. Perhaps life itself is indeed a long, beautiful ritual of giving back tears.

The course of life may seem written, yet we remain emotional beings. As women, through birth, we pass our water into new lives. But all of us, each in our own virtue, give what we can.

I was born and raised in the North, where winter reigns for five months each year. My homeland swarms with children of forest and moonbeam, drunk philosophers, whispering witches and gods of death. Welcome to the realm of northern water: here, we sense poetry of dying and revival as the wind passes through our bodies.

The miraculous occurs in winter, for everyone is navigating survival. As the world freezes, the fairy tale unfolds. Landscapes crystallize, sharp and transparent. Heaven, earth, and hearts transform into a vast mirror of ice. Here, we long to become truly ourselves—everything around us is bare; nothing within us can remain hidden.

Water is often perceived as a metaphor for the unconscious—an ancient well reflecting our true selves. To gaze into water is to confront darkness hidden beneath masks. It awakens lost aspects of personality—an encounter with unimaginable inner gods—raw, authentic, sometimes unsettling. Water urges our spirit swollen with pride and anxiety to return gently to peace.

Carl Jung wrote: But “the heart glows,” and a secret unrest gnaws at the roots of our being. In the words of the Völuspa we may ask: What murmurs Wotan over Mimir’s head? Already the spring boils…

Water’s Yin-Yang duality defies clear definition. If anything can be confidently stated, it is this: water is nonbinary. It dissolves distinctions, embracing opposites within itself. Water is seed and womb, instinct and intuition, arousal and release.

Curiously, Wu Xing philosophy assigns water as the essence of masculine sexuality, represented in the North by the Black Tortoise (玄武). This is even funnier when considering men hunt sea turtle eggs hoping to enhance their virility. Water resides in the kidneys, representing instinctive desire, animal breath, blood flow, and mercurial temperament. A passion that is tangible and real, a wisdom that can be soft and humble—qualities seemingly aligned with “yin,” yet collectively defining masculine “yang.”

Globally, however, water embodies feminine power. Freshwater symbolizes fertility, emotional intelligence, care, and lineage. Rivers are mothers; wells are wombs; rain is lullaby. In myths, goddesses are born from foam and springs. In reality, women bathe newborns, cleanse wounds, weave stories.

Water’s power manifests precisely through paradox. Even the most rational man feels the tides within; even the most reserved woman carries storms. Water inspires commerce, conquest, communication. My favorite metaphor, Venice, miraculously built upon water, embodies this paradox—merchants mastering sea voyages while carefully preserving freshwater from the sky, sustaining a civilization through fluid generosity.

Water refuses division, endlessly dissolving distinctions and merging them anew. It expresses this profound virtue through humility and musical sound. Ancient philosophers thus persuaded us to “be water,” to embody duality through motion, never through opposition.

The phrase ‘Be water’ resonates widely, capturing the human imagination across different cultures and epochs. People seek to become water, to flow authenitically and freely, toward the rhythms of time and nature.

In Chinese culture, there’s a special word: 风流 (fēng liú). Literally translated as “wind and stream,” it carries richer shades of meaning—an elegant romantic freedom, a natural ease with life, a gentle embrace of existence. When we describe someone as possessing fēng liú, we might mean they’re amorous or poetically erudite, yet always attuned to life’s subtle movements. Sensitive to elusive beauty, graceful and free, they move fluidly between deep affection and quiet detachment, indifferent to mundane expectations or social clichés.

风流 (fēng liú) evokes the essence of Eastern aesthetics, revealing romance in a manner of “wind and stream.” Thus, it’s perfectly logical that the Chinese transliteration of “romantic” (浪漫, làng màn) uses the radical for water (氵). 风流 (fēng liú) isn’t concerned with mundane obligations; instead, it embodies a sincere rhythm arising spontaneously within each fleeting moment. Wind and stream resonate gently with everything around us, endless fluid, fulfilled in ethereal beauty. There’s a phrase I particularly adore: “不著一字,尽得风流” (Without writing a single word, the spirit of fēng liú is fully expressed). I love how subtly it conveys that elegance and emotional depth require innate talent, rather than explicit articulation.

In A Short History of Chinese Philosophy, Philosopher Feng Youlan (冯友兰) struggled to translate this concept precisely. He noted that the literal meanings—“wind” and “stream”—hint at an unrestrained and flowing nature central to Taoist thought. It’s widely understood that Taoism encourages us to move fluidly, harmonizing effortlessly with nature, remaining humble, adaptive, and receptive. Water reminds us to sense the current of all beings—every entity, even lifeless ones, quietly possesses a soul.

Over time, I began to grasp how differently Western romanticism is portrayed. Its root, “Roma,” originally signified embodying something Roman: passionate, dramatic, impulsive—even animalistic. If Eastern fēng liú gently navigates existence through subtle animistic sensitivity, Western romanticism plunges boldly into human passion—desire, conquest, sensuality, power, and raw collective truths. Its image is not a gentle stream, but rather the Colosseum, a place where human nature confronts beauty and brutality openly, without disguise.

Whether we seek authenticity through passionate expression or wish to embrace a free spirit attuned to all things, both paths ultimately lead us back to the bittersweet exploration of human nature itself. Each of us carries a distinct metaphor within, irrespective of cultural origins. A spark ignites when we begin to wonder: what kind of romantic are you? What sort of Rome resides inside your soul?

Still, we cannot escape water’s gentle lesson. Taoism’s ancient wisdom whispers quietly yet persistently: “Be water.” It encourages us not to cling stubbornly to morality, nor succumb to hypocrisy; not to suppress passions, nor lose ourselves entirely within them. Instead, We must flow freely—open, unbound, curious and caring. And when the world around us is waiting to be rediscovered, we may also start to sense the deeper currents that carry us beyond life itself.

The unborn child, suspended in amniotic fluid, experiences the most primitive, intimate, and secret moment of existence. Every soul first takes form in these unconscious waters, slowly ascending toward the conscious flames. After birth, we gradually construct rational structures to define ourselves—yet beneath consciousness, primal waters persist, indifferent to distinctions like good or bad, inner or outer, dream or reality.

These ancient waters embody eternity itself. I once read accounts from caregiving nurses describing patients approaching natural death.

As their time draws near, they often sleep deeply, drifting between worlds—half in reality, half already beyond. They appear tranquil, gently releasing their grip on consciousness, experiencing moments of connection to a timeless space. These descriptions left me weeping at the wordless tenderness with which nature guides us softly back to the very state from which we first emerged. It echoes exactly the peace of an unborn child floating in amniotic darkness—untouched by thought or fear.

Returning to these eternal waters, everything around us turns dark. Life reveals itself as an extraordinary cycle. All the narratives, the mathematics of life and creation, miraculously align within this quiet stream. We flow gently in the current of being, the waters inside us merging, communicating beyond memory or recognition. For no matter what we have conquered, no matter who we have become, a timeless, sacred essence ultimately rules our destiny.

Explore other elements