Metal carries meanings. Drawn from earth, refined by fire, the boundary of civilization is shaped by metals. In nature, no substance is truly pure, yet humans obsessively yearn for purity and new combinations. Over centuries, this desire has only deepened, sharpening our definition of value itself.

Metal symbolizes worth, permanence and glory. The Chinese character 金 (jīn) means “gold,” yet its philosophical meaning encompasses silver, bronze, iron—any precious matter transformed through human intent. Metal is the deity of autumn, cold and exacting—the blade of judgment, the precise nib that enforces law and order, and the ritual instrument distinguishing right from wrong. It also appears in poems—as the pale silver moon, frost glittering softly on harvested fields, and the solemn westward journey beneath twilight skies.

Among the Wu Xing (五行), wood and fire represent ideas and passions—fluid and shifting—while water and metal firmly ground us in essential reality. This contrast reveals a dance between idealism and materialism. Fire overcomes metal, yet metal depends upon fire; only flame unlock metal’s full potential, transforming it into something complete and purposeful. Meanwhile, metal grants fire a vessel, containing its wild spirit and giving form to its fantasies.

Compared to the four-element framework, Wu Xing replaces air with wood and separates metal from earth. While wood symbolizes coexistence with nature, metal signifies a profound shift—from passively observing the world to actively reshaping it. Metal implies and encourages domination, becoming the alchemist’s obsession: extracting from earth to craft purity itself—dualistic and perfect.

Why are humans so irresistibly drawn to metals? They are rare—atoms repeatedly forged in distant stars, scattered across planets, buried beneath the earth, waiting to be discovered. Yet to reach these cosmic treasures, we first had to solve riddles of fire, mathematics, and craft. Gradually, we found romance in their purity, eternity, and noble essence. Eagerly and sincerely, we chose metal to preserve our legacies.

Alchemy holds an unwavering position in both Eastern and Western cultures because it symbolizes the magical act of transformation itself. By melting and molding shining earth, our ancestors unlocked hidden powers: stones sharpened into blades, soil transmuted into cities. Ambitions intensified, humans longed for something divine, believing that sacred, unknown metals born from their furnaces could grant eternal life. Ironically, this pursuit often shortened their mortal years.

Bronze idols became gods, iron forged empires, coins conjured economies, human developed diverse tools and reshaped entire landscapes. A pivotal moment emerged distinctly between the Neolithic and Bronze Ages—a historical shift from honoring the earth’s generosity to mastering and dominating it. Humans turned from mother goddesses toward warrior kings, from fertility cults toward imperial conquest. With metal came civilization’s true alchemy: the rise of patriarchy, hierarchical power, and the ethos of conquest. Metal didn’t merely participate civilization; it reshaped the very idea of what civilization meant.

In Wu Xing, metal (金) isn’t constrained by the periodic table. It encompasses all refined substances—iron, copper, jade, crystal—everything reshaped through human technique, discipline, and intentionality. Therefore, clay pottery remains earth-bound, but glazed porcelain is elevated into metal’s domain.

Among all the metals, Chinese culture reveres jade most profoundly. When Nüwa mended the heavens, she selected five-colored stones symbolizing the five virtues and elements, granting jade enduring spiritual and political significance. Imperial seals, ancestral tablets and sacred pendants were all crafted from jade, a mineral close to earth, treasured for modest beauty, purity, and moral resonance. Jade absorbs warmth but refrains from gaudy brilliance.

The West, on the other hand, historically craved gold. Glittering splendidly in riverbeds, gold represents tangible reward for labor. Empires chased it across oceans, igniting colonization, slavery, and birth of banking systems. While jade faithfully adorned temples and embodied period virtues—often buried in tombs alongside its owners—gold openly fueled ambition and material desire, placing scales and markets above morality itself. Metal thus profoundly reshaped humanity—dictating who we became, what we valued, and how we chose to live.

Metal overcomes wood. As Humans swung their axes, forest fell. Fire ignited, and with them arose illusions of endless expansion. Ideas and Virtues traveled overseas, alongside innovations, warfare and disease. For thousands of year, violence defined metal’s legacy. Glory required conquest, and conquest involved murder.

Yet from those mountains of accumulated wealth emerged a subtler form of dominance—softer, but equally powerful: the authority wielded by money, eduction, moral standards, and enforced ideas of “perfection”.

Metal embodies wealth, and wealth can transform into authority (财生官). When wealth largely remains as wealth, capitalism arises—a society fluid, mercantile, and opportunistic. And when wealth crystallizes into institutional authority, oligarchies or monarchies emerge, hardening social structures. Nevertheless, authority also fosters constructive outcomes: public services, educational systems, collective norms—rare achievements from humanity’s turbulent experiments.

I am always disturbed by how unimaginative and cold-blooded the authority can be, and how money reshapes circumstances entirely. Yet as time passes and scars sink underground, we again become astonished by the accomplishment inscribed upon milestones. Historic narratives—soft power manipulated by a select few, communicate both the best and worst outcomes of men’s decisions. We glimpse no unvarnished truth; every civilization emphasizes a chosen tone, repeating fixed chapters—stories incomplete, incapable of making us whole. Wise individuals are destined to outgrow the social roles quietly crafted by metal’s disciplined creativity, creating their own balanced worlds amidst an unbalanced civilization.

The soft power of metal profoundly influenced gender roles. In Chinese Bagua (八卦) philosophy, Qian (乾, heaven) represents yang metal—authority, idealized strength, glorious dominance. Kun (坤, earth) signifies mature femininity—motherly, supportive, and nurturing. Yet another feminine archetype emerged in Dui (兑, lake or yin metal): joyful, youthful girls admired yet restrained by artificial standards of femininity.

This “yin metal” symbolizes delicate beauty upheld by the patriarchal gaze: ornamental, refined, fragile. Men, enamored of their metallic ideals, projected a softer reflection of their rigidity onto women: charmingly submissive, contentedly restrained, shimmering elegantly on the surface. Such femininity is artificial—it confines women, stripping away natural power and substituting authenticity with decorative brilliance.

Photo by 盾乙 / Weibo

Restricted in golden shackles, women faced two narrowly authorized roles: Kun (坤, earth), the mother, or Dui (兑, metal) , the eternally youthful, dreamlike girl.

Although metal itself appears eternal, this idealized femininity swiftly vanishes with age. Yet the desire to become radiant gems remains engraved over millennia into our bones—itchy, painful, and persistent—dictating internalized ideals of femininity.

When humans drew clear boundaries between metal and earth—placing transactional value above the vital connections that nurture all existence—women’s natural roles as protectors of land and water were likewise undermined. Reclaiming women’s innate strength might offer a key to breaking these artificial metal cages and restoring ecological harmony. Only then might we truly appreciate metal’s potential—not just in creating formalities or enticing adventures, but also as a means of understanding, healing and wellbeing.

I dreamed of the Mother of earth walking amidst chaos. She gazed upon towers of polymers, glass and steel relentlessly rising from her lands. Raising her hands, she performed a merciless vasectomy upon these monstrous structures, quietly yet firmly declaring: “That’s enough—this wretched ugliness shall not spread further.”

Image by Smithsonian’s National Zoo, via Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0.

Our metal-like creations have grown increasingly outrageous, detached from nature, descending into realms of artifice and absurdity. Humans imitated volcanic craft, making elegant glass—drawn from sand, reshaped by fire—embodying transparency, fragility, and boundless utility. Yet at the extreme end of our obsessive alchemy, we birthed plastic to fuel rapidly growing modern industry. This synthetic material, unnaturally derived from petroleum, eventually revealed its true form—a killing weapon disguised as convenience, infiltrating oceans, wildlife, and even our own bloodstreams.

Simultaneously, humans uncovered new metals from the depths of atomic order—Rare Earth Elements, potent minerals now powering our most sophisticated technologies. The craving to master atoms and harness immense energy drove led us to nuclear power, presenting both extraordinary potential and catastrophic threat. Eventually, we crafted microchips from silicon—an earthly element so common yet practical, we became utterly dependent upon it. Today, intricate metallic patterns invisibly govern our daily lives, building virtual worlds and intangible wealth.

By dancing with atoms, we have embraced powers akin to miniature stars and black holes, our circumstances propelled by unpredictable solar winds. We now stand before Pandora’s box, irresistibly drawn toward unknown futures where our valuable yet fragile cultures could flourish—or vanish entirely.

We shape metals, yet metals shape us far more profoundly. Galileo Galilei once whispered, “Eppur si muove”—“Yet it moves.” Every living being and surrounding existence moves inherently, yet many today, driven by golden dreams and mechanical impulses, move only because authority shakes the plastic box encasing their minds. Their biological codes no longer compose new symphonies; their structures house no soul.

We can no longer entertain optimistic futurology. Instead, we find ourselves undoing the artificial world that imprisons and harms us, with only the very metals into which we poured our finest minds and energies remaining as tools.

Perhaps, finally, we must truly learn the nature of metal itself. Despite the price exacted by our reckless desire and limited wisdom, metals remain beautiful creations born from universal alchemy. Now, more urgently than ever, we must use their potential to heal the soil and water—our earliest realities, the tangible foundations of life—which have for eons maintained the harmony connecting all forms. This time, we still need their help.

In Indigenous worldviews across continents, metal extraction required ceremony and reciprocity—taking from the Earth demanded giving in return. Miners of old entered mountains understanding themselves as guests in sacred bodies, not conquistadors entitled to endless treasure. The ritual of asking permission acknowledged a relationship between taker and taken, something industrial processes systematically erased.

The ancients understood what modernity has forgotten: metal must eventually return to earth. The blade will inevitably rust, releasing its refined essence back into the soil, completing a cycle essential for wholeness. Our error was not in crafting metal but divorcing it from cyclical existence—we refuse its graceful return, instead forcing metal to burn endlessly within flames and digital lights. Sharpened into wealth and currency, metal has divided our world and fractured our reality.

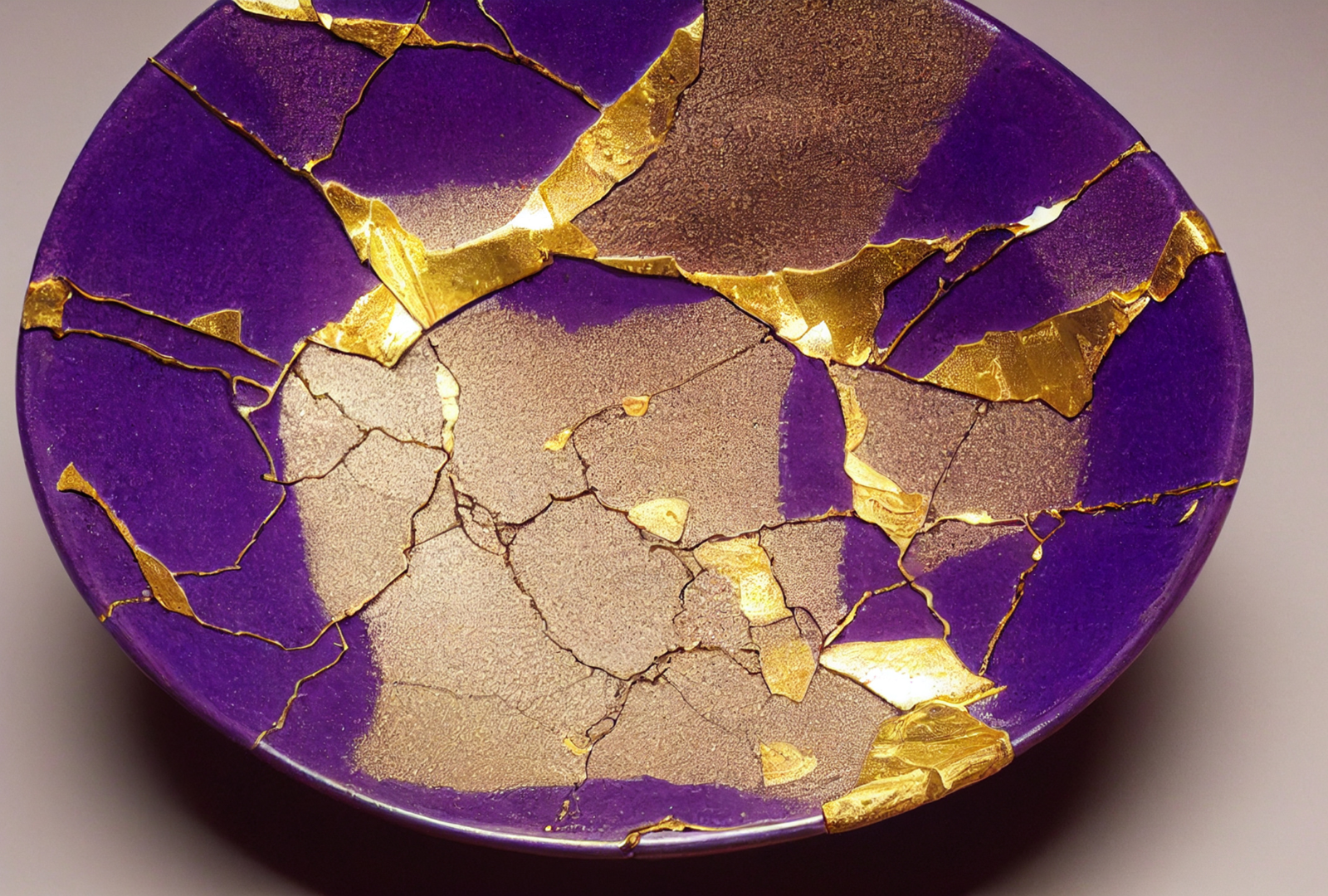

Yet the same precision and refinement that created weapons can forge solar arrays; the same gold that once drove colonial conquest can now conducts electricity in devices measuring ecological health. Metals hold infinite readiness to heal. The Japanese art of kintsugi offers a compelling metaphor for this renewed relationship. When precious ceramics break, artisans mend fractures with gold, creating objects more beautiful precisely because they’ve been damaged. Rather than concealing imperfection, this practice honors the journey of healing, visibly integrating past injuries into a new wholeness. Perhaps this represents our path forward—using metal to heal Earth’s wounds, making our processes of repair transparent, visible, unforgettable, ensuring we avoid repeating our destructive mistakes.

In the alchemist’s wisdom, the final stage of the Great Work was never about hoarding gold but achieving integration—the reconciliation of opposing forces into restored harmony. We must regard metal not as the world’s capital but as nature’s brilliant child, just as humans are. Despite our toxic impulses, we remain a species of extraordinary brilliance and potential. It’s now essential, urgently, to prove this—to the world, and to ourselves.

Explore other elements